Learning about Shinto through Architecture

Shinto - "the way of the kami" - is deeply rooted in pre-historic Japanese religious and agricultural practices. The term kami can refer to Japanese mythological deities, but also can mean divinity manifested in natural objects, places, animals, and even human beings. Shinto rituals and celebrations stress harmony between deities, man, and nature -- a key feature of Japanese religious life and art to the present time. This page uses the architecture of Shinto shrines as a window into Shinto practices and worldview. Materials presented here were developed by teachers in a year-long ORIAS program, Teaching Comparative Religion Through Art and Architecture.

This page is divided into seven illustrated sections:

Harmony with Nature: Shinto Sites

First Structures: Early Shrine Architecture

The Geography of Sacred Space: Shrine Complexes

Influence of Buddhism: Syncretism in Architecture

Organization of Sacred Space: The Ritual Landscape

Nachi Falls is a sacred space for Shinto. The falls were originally devoted to kami verneration. Today they are also associated with the Buddhist bodhissatva of mercy, Kannon. The rope over the top of the falls is a shimenawa, marking the site as sacred.

Seiganto-ji pagoda is a Buddhist temple. Nachi Falls is visible in the background.

The Nachi Shrine is a Shinto/Buddhist multiplex. Indigenous practices of Shinto gradually incorporated imported practices of Chinese Buddhism. The syncretic history of Japanese religion can be seen in the evolving architecture of sacred spaces.

(1) entrance gate featuring a torii or a Chinese-influenced two-storey romon, (2) stone stairs, (3) pathway (sandō), (4) washing place (chōzuya), (5) lantern (tōrō), (6) Kagura dance platform (kagura-den) building dedicated to Noh or the sacred Kagura dance, (7) shrine office (shamusho), (8) votive picture repository (ema-den) where worshippers leave small wooden plaques (ema), (9) auxiliary shrines or under-shrines connected to larger shrines (sessha/massha), (10) stone lions (komainu) - of Chinese origin, (11) worship hall (haiden), (12) fence surrounding the shrine (tamagaki), (13) the sanctuary, most sacred building (honden or shinden).

The grand scale of the Heian Shrine in Kyoto shows the influence of Buddhist architecture and the support of noble patronage.

This torii at Asakusa Buddhist temple is an example of an eight-post gate.

The curved roof and ornamental detail of Tarumaesan Shinto shrine shows the Chinese architectural influence imported with Buddhism.

The Ishidorii (Stone Gate) at the entrance to the Toshogu Shrine was dedicated in 1618.

Shirahige Shinto shrine, located on the edge of Lake Biwa, features a torii in the adjacent lake.

Torii and sando at the Meiji Shrine in Tokyo.

Fushimi Inari-taisha Shinto shrine features a pathway lined with thousands of torii. The pathway connects the main shrine to the inner shrine.

Purification at chozuya before entering Meiji Shrine

Chozuya (washing place) at the Yahiko Shinto Shrine

The honden at Izumo Shrine is the tall building on the left. The other buildings are smaller shrines. All of them are surrounded by fences, making them inaccessible to visitors.

The haiden at Izumo Shrine. The sacred ropes hanging over the front entry are twisted together from rice straw. Called shimenawa, they are used to mark a sacred precinct. They are traditionally believed to ward off evil and sickness. At New Year's people hang them over doorways or the front bumper of cars.

Offerings of mochi (rice cakes) at the Meiji Shrine. Each pair of cakes is stacked on top of a sanbo, a wooden stand for food offerings.

This image of Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine shows both ema (wooden plaques with prayers written on them) and omikuji (strips of paper with fortunes written on them). Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine complex is now dedicated solely to Shinto, but for most of its history the location hosted both Buddhist and Shinto buildings. This changed with the 1868 Kami and Buddhism Separation Order.

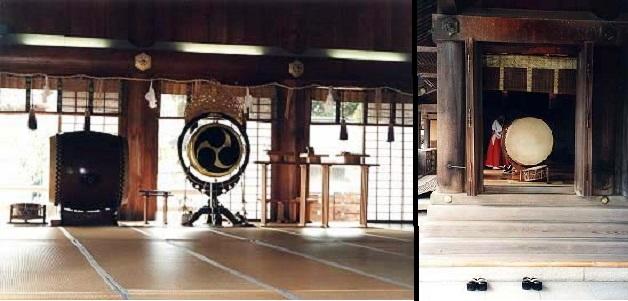

Music Hall (left) and Music Platform (right)

Every 20 years the Ise Shrine is rebuilt on the adjacent lot. This model shows the existing shrine alongside the kodenchi, which is the (temporarily) empty site of the previous shrine.

2013 was a rebuilding year for Ise Shrine. The empty site from the previous shrine, the kodenchi, is marked by a small wooden building. When the shrine is rebuilt again in 2033 this building will mark the center of the rebuilt shrine.

Two views of the Geku (outer) Shrine at Ise. On the left is a view from 2013, just before rebuilding. On the right is a view from 2018, five years after the new construction. For additional images of the shrine comples, see the official Ise Jingu website.

The nishi-jukusha at Izumo Shrine is a building to house the gods during the Kamiari Matsuri festival in October.

This view of the Izumo Shrine shows the high-floor dwelling style of the honden. Just to the left of the taller building, you can see the slanted roofline of a long narrow hall leading up into the building.

Note the curved roof line and ornaments of the Izumo Shrine.

Image Credits & Bibliography

Images

Header: Jun Seita DP0Q0641 via photopin (license)

View of falls with shimenawa: inefekt69 Nachi Falls - Wakayama, Japan via photopin (license)

View of falls with building: Laruse Junior Seiganto-Ji Pagoda via photopin (license)

Imperial Ise shrine: Bernhard Sheid Ise, Old and New via flickr

Nachi Shrine Complex: David Z. Nachi Taisha via flickr

Ainu Museum building: Saldesalsal Purotokotan Ainu Museum via flickr

Plan of Shinto Shrine: wikiwikiyarou Plan of Shinto Shrine [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Drawings of Izumo Shrine Complex: Robert Treat Paine and Alexander Soper, The Art and Architecture of Japan. Yale University Press, 1981. P. 283.

Eight-post torii at Asakusa Buddhist Temple: Nelo Hotsuma Asakusa via flickr

Heian Shrine in Kyoto: Zhang Wenjie Heian Shrine via flickr

Ishidorii at Toshogu: Images George Rex Ishidorii/Nikko via flickr

Torii in Lake Biwa at Shirahige Shrine: inefekt69 Takashima, Japan via photopin (license)

Torii pathway at Fushimi Inari-taisha Shinto Shrine: Dariusz Jemielniak ("Pundit") [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Meiji Shrine torii and sando: Yasuyuki Hirata The Grand Shrine Gate of Meiji Jingu via flickr

Purification at Meiji Shrine: FujiChallenger Meiji Jingu Chozuya via flickr

Purification at Kiyomizu: Donna Kasprowicz

Chozuya at Yahiko Shrine: jpellgen (@1179_jp) Yohiko Shrine: Chozuya via flickr

Honden at Izumo Shrine: u-dou jap2016 nov 08 izumo (57) via photopin (license)

Haiden at Izumo Shrine: Miya.m - Miya.m's photo, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Mochi offering at Maiji Shrine: Gautsch Mochi, detail via flickr

Ema and Omikuji at Tsurugaoka Hachimangu: Gilles Vogt Temple shinto à Kamakura via flickr

Music Hall and Music Platform: ORIAS archives

Wooden model of Ise Shrine: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra Sanctuaire shintoïste Ise Jingu (exposition Fukami, Paris) via flickr

Kodenchi at Ise Shrine: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra Le futur site du sanctuaire intérieur d'Ise (Japon) via flickr

2013 View of Geku at Ise: Ye-Zu Ancien et nouveau via flickr

2018 View of Geku at Ise: nobu3withfoxy 外宮 Geku/Ise Jingu via flickr

Bibliography

Earhart, H. Byron. Japanese Religion: Unity and Diversity. Third Edition. California: Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1982.

Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Tokyo: Kodansha Ltd. 1993.

Nelson, John. 2000. Enduring Identities: the Guise of Shinto in Contemporary Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Paine, Robert Treat and Alexander Soper. The Art and Architecture of Japan. Yale University Press, 1981.

William, Alex. Japanese Architecture. New York: G. Braziller, 1968.