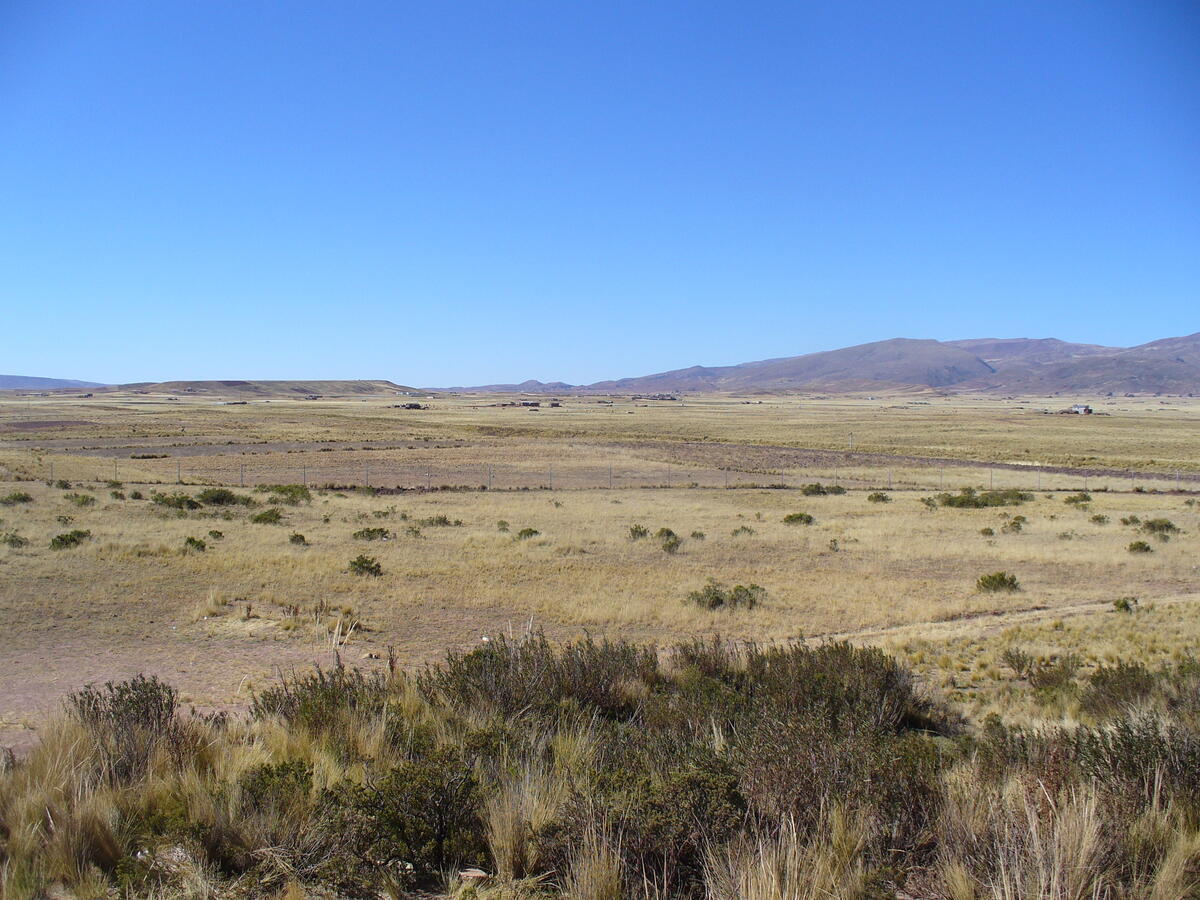

Location: Altiplano in Bolivia

My name is Nicola Sharratt. I’ve been an archaeologist for more than 20 years. I grew up in England, in a city with a medieval cathedral, a castle, and buildings that were hundreds of years old. Although I liked being surrounded by so much evidence of the generations of people who had lived there before me, I planned to become a lawyer when I finished school.

That all changed when I was 17 and joined an archaeological project as a volunteer during the summer. We were excavating a Roman military camp. The soldiers who camped there were ordinary people; most of them were privates who were hundreds of miles from home. Their experiences weren’t written down; we don’t have their letters or diaries. But archaeology made it possible for us to find out what army life was like 2000 years ago.

That experience made me understand that archaeology is important. Archaeology lets us discover and tell the stories of everyone, including all the people who weren’t rich or powerful enough to be written about. I also realized then that archaeology is a real career! And that I could study it in college and spend my life investigating and telling others about regular people, people like those Roman soldiers and people like you and me.

Today, I’m a professor at Georgia State University in Atlanta. I love teaching college students about people in the past. Although I first did archaeology in England, since then I’ve been fortunate to work on projects in Tunisia, Argentina, Bolivia and most of all in Peru. In this kit, we’ll explore the Tiwanaku (~400-1100 CE). Tiwanaku people lived in parts of what today is Bolivia, Peru, and Chile.

We’ll start by looking at the incredible landscape that Tiwanaku society began in. We’ll see how ideas about Tiwanaku’s biggest city have changed over the past 100 years. We’ll look at how Tiwanaku farmers found ingenious ways to grow crops in a challenging environment, and how some of those techniques are still used today. We’ll follow Tiwanaku migrants as they made new lives in distant regions. Finally, we’ll think about how regular women and men in Tiwanaku towns brought about political change and built a new, more equitable society.

I hope this Tiwanaku kit shows you how creative, determined, and resilient all of us can be!

Nicola

Field Crew, 2015. The author is in the back row, 4th from the left.

Archaeologists are always interested in where ancient people lived. Physical environment and climate affect what crops we can grow, the types of shelters we have to build, and other kinds of cultural adaptations, like special clothing or sunscreen, that we need to live comfortably in certain environments.

Tiwanaku society emerged in an area in Andean South America called the altiplano (high plain). It is named the altiplano because it is at high altitude. Altitude means how many meters above sea level a place is. I live in Atlanta which is 225 meters (738 feet) above sea level. If we’re used to living at lower altitudes (like Atlanta), it can feel uncomfortable to go to a high-altitude place. We have to work harder to breathe. It’s difficult to run or do physical exercise. People may get headaches. Denver is the highest altitude city in the USA and it is 1600 meters (5249 feet) above sea level. That is high enough that some visitors to Denver feel the effects on their body.

But that’s nothing compared to the altiplano! Tiwanaku emerged in a part of the altiplano called the Titicaca Basin. It’s named for Lake Titicaca which is the highest navigable lake in the world. The lake is at almost 4000 meters (13,123 feet) above sea level!! So much higher than Denver!! It’s also pretty windy and cold in the Titicaca Basin. At night, the temperature can get well below freezing. Plus, it doesn’t rain very often. In other words, Tiwanaku people had to develop some very creative cultural adaptations to live comfortably in this place. Later, we’ll see how Tiwanaku farmers figured out how to farm successfully in this environment.

People first started to live in this region around 10,000 years ago (or 8,000 BCE). They were hunter-gatherers. Instead of living in villages or towns, they stayed in short-term camps and survived by eating wild animals like guanaco and vicuña. Around 4,000 years ago (2,000 BCE), some people built settlements on the shores of Lake Titicaca. The lake has lots of tasty fish and wild ducks so it’s a good source of food for dinner!

Over the next 1000 years, people began to build courts partially sunken into the groundat their settlements where they could come together and worship. We don’t know exactly what gods they believed in but because we see very similar imagery on sculptures at many different villages, we think that they probably shared religious beliefs. One image that shows up in different places is called Yaya-mama. It shows two figures together, probably one male and one female.

Figure 4. A Yaya-mama statue

Image by Pavel Špindler, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Around 500 BCE, two sites (Pucara and Tiwanaku) became much larger than the others. We’re not quite sure what the relationship was between people at Pucara and Tiwanaku. It is possible there was warfare between them, but we don’t yet have enough evidence to know for sure.

If people living at Pucara and Tiwanaku were in competition, Tiwanaku came out as the winner. By 400 CE Tiwanaku was the biggest and most important site in the Titicaca Basin. From this point, it grew into a big, diverse city. More ritual structures, including a huge pyramid called the Akapana and large open air plazas, were built. Religious leaders gave their gods offerings of llamas and other valuable items by burying them on top of the Akapana.

Tall carved stone statues were placed in some of the plazas. These statues depict humans holding drinking vessels called keros. One way that leaders in many times and places try to persuade people that they should be in charge is to throw big parties with lots of food and drink. Lots of politicians do this but Tiwanaku leaders seem to have especially relied on this tactic! Not only did they host parties, they made statues like this one that reminded people they gave great parties. As we’ll see later, it didn’t work forever….

Tiwanaku stone carvers were skilled and their work was visible all over Tiwanaku! People walking through the Sun Gate would have seen this carving of the Staff God. Look closely at him. Can you see the snakes coming out of his headdress? Archaeologists named this figure the Staff God because the individual with the headdress is holding a staff in each hand. We don’t know exactly how people in Tiwanaku would have described the Staff God. But all those figures with wings flying around him suggest he was pretty important.

Tiwanaku architects made the city a place that people wanted to come to. Some came for a short visit to watch the rituals and to join in the parties. But as many as 20,000 people also lived at Tiwanaku. Some of those people were very wealthy. Tiwanaku’s richest residents lived in a palace called the Putuni. The houses of the palace were painted. It even had a drainage system so the wealthy people didn’t have to smell dirty water. The folks living in the Putuni had really fancy pottery and items made of copper, silver, and pretty shells. Many of those objects were imported from long distances.

Like cities today, regular people lived at Tiwanaku as well. Their houses were arranged in neighborhoods. The richer neighborhoods were closer to the center of the city. The less wealthy homes were on the edge of the city. Houses had kitchens and outside patios. They also had space for a family’s animals including alpacas and guinea pigs.

Tiwanaku was a large, busy city. In another section, we’ll look at the countryside around Tiwanaku. We’ll also see that some Tiwanaku people migrated hundreds of kilometers from the city to start new lives elsewhere.

Archaeologists aren’t the only people who care about the past. For hundreds of years, Tiwanaku has been important to different people for different reasons.

If you look back at the timeline, you’ll see that Tiwanaku leaders were overthrown around 1000 CE. Over 200 years later a new political power base, called the Inka, began to expand its reach outward from their base in Cuzco (in modern Peru). Eventually the Inka Empire extended along the Pacific coast of South America and into the Andes, including the Titicaca basin. According to a Spanish author, Bernabé Cobo, writing in the 1600s CE, when the Incas first arrived at Tiwanaku from Cuzco in the 1400s CE, they were fascinated by the abandoned buildings and statues. They even incorporated Tiwanaku into one of their creation stories. They said that the god Viracocha came out of Lake Titicaca. The Incas thought that the stone statues at Tiwanaku were the remains of giants that Viracocha had created before he made Andean people. In other words, they believed Tiwanaku was part of their distant past.

The Spanish overthrew the Inka leadership in the 1530s. They also seem to have been interested in Tiwanaku. In 1553 CE, the Spanish writer Pedro Cieza de Leon described visiting a site with large buildings and huge stone statues. Sound familiar? We think he was writing about Tiwanaku!

In the 19th century, travelers and scientists from Europe visited Tiwanaku. The altiplano was a very different environment from what they were used to in Europe. Some of these visitors claimed that Tiwanaku could never have been a busy city because the climate was too harsh. Others suggested that the site was originally on the coast but that tectonic activity had moved it to the altiplano. These Europeans just wouldn’t believe that the ancestors of the Bolivian communities they encountered could have built and lived in a big city.

Those Europeans were wrong. Tectonic activity cannot move an archaeological site from one location to another. In the past 100 years archaeologists from Bolivia and other countries have shown that the incredible city of Tiwanaku was definitely built in the altiplano. It was also definitely built by people from the altiplano. Archaeology makes it clear that skilled architects from Tiwanaku made the plazas. They built the stone buildings and statues.

Their descendants and other Bolivians still care about this past.

Today, there is a town located next to the ancient city of Tiwanaku. Some of the town’s residents are descended from the people who lived at Tiwanaku 1500 years ago. For them, the site is an important part of their identity. Their ancestors built it. They are proud of that.

Tiwanaku is also important to other Bolivians, as well. For example, in 2005, the Bolivian president was sworn into office at Tiwanaku. He was a member of the Aymara, an Indigenous ethnic group from the altiplano region. He chose the site because of what it symbolized. Tiwanaku was built by Indigenous people 1000 years before the Spanish conquered South America. By being sworn in there, he wanted to show that 500 years after the Spanish conquest, Indigenous people were in power again.

We saw earlier that Tiwanaku emerged in a cold, windy, high altitude environment called the altiplano. Because of that, some Europeans didn’t think it was possible there was a society there. They didn’t believe a big population could have survived in the altiplano. Those 19th century travelers didn’t understand how to make a living in the altiplano. But Tiwanaku people did. And people living there today also know. For meat, Tiwanaku families raised alpacas and guinea pigs to eat. Alpacas and llamas like high altitudes, so the altiplano is a perfect place for them. Families also ate fish and wild duck from the lake. It’s true that it isn’t possible to grow some crops, like maize, in the altiplano. But there are lots of other crops that do grow there. People in the past and the present grow food such as potatoes and quinoa (pronounced keen-wah)

To farm successfully, Tiwanaku men and women had to create special kinds of fields. During most of the year, it doesn’t rain very much in the Titicaca Basin. But during the short rainy season (November to March), crops can get flooded if too much rain falls. To protect their crops, people built raised fields in the countryside around Tiwanaku. The soil is piled up in rows above ground level. Between the rows are ditches where rain water can flow without hurting the plants. The raised soil also helps protect crops from the cold nighttime temperatures. This technique is so successful that some families living in the altiplano today still use raised fields. Some archaeologists think those raised fields prove that Tiwanaku leaders organized and controlled farming. But modern farmers who build raised fields generally manage to cooperate and organize themselves to work together. That type of farming is not necessarily a sign of centralized control.

Figure 11. Raised fields in the altiplano in Silustani, Peru

Image by Pedro Szekely, (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Even though tasty and nutritious crops grow in the altiplano, Tiwanaku people wanted a crop that doesn’t grow at high altitude – maize (commonly called “corn” in the United States). Maize was important to Tiwanaku leaders because it was used to make beer. And remember that Tiwanaku leaders threw a lot of big parties!! So, they needed maize to fill their keros.

People migrated from Tiwanaku to other places where maize and other lower altitude crops can grow. Tiwanaku objects are found in the Cochabamba Valley in eastern Bolivia. They’re also found in San Pedro de Atacama in northern Chile. But most migrants traveled about 350km (215 miles) from the altiplano to the Moquegua Valley. (See the map above to locate Moquegua). Today, this is in Peru. You can see from this picture how different the landscape and climate is from the altiplano. Tiwanaku families settled at a much lower altitude than the altiplano, about 1500 meters (4920 feet) above sea level. Maize grows well in the Moquegua Valley.

Like many migrants today, Tiwanaku people took their customs and traditions with them. They and their descendants organized their towns and houses in similar ways to the city of Tiwanaku. They built smaller versions of the ritual buildings at Tiwanaku. They made and used similar styles of pottery. They decorated their objects with images of animals from the altiplano. They buried their dead following the same kinds of funerals as their relatives in the altiplano. Continuing to follow practices from their homeland was an important way of keeping their identity as Tiwanaku strong.

These artifacts and burial practices are important evidence for archaeologists that there were Tiwanaku people living in the Moquegua Valley. Even stronger evidence comes from analyzing human bone and teeth. The specialists who study human remains are called bio-archaeologists. Bio-archaeologists can study the chemistry of bone and teeth to find out what people ate and whether they migrated during their lives. Some of the people buried in Tiwanaku cemeteries in Moquegua grew up in the altiplano and moved to Moquegua as adults. Others were second or third generation immigrants and had been born in the Moquegua Valley.

There were already people living in Moquegua when Tiwanaku people arrived. There were also migrants from another society, called the Wari, living in the Moquegua Valley. Archaeologists have some evidence that these groups of people interacted with each other, although interactions seem to have been quite limited. For example, archaeologists have found Wari-style pottery in a few Tiwanaku burials in Moquegua. How might you explain this? What might it mean about how people from different backgrounds interacted in Moquegua?

Archaeologists have some ideas. Maybe people from the two societies married each other. Maybe Tiwanaku and Wari men and women traded goods, including pottery. Or perhaps Tiwanaku and Wari potters sometimes copied each other’s styles. Consider ways people from different backgrounds interact in your own community. Can you think of any other explanations?

Remember those parties with the maize beer? We think Tiwanaku leaders held them partly to persuade the population that the leaders should be in power, and also to reward people for doing work (like construction or farming). That tactic worked for a few hundred years. But around about 1000 CE, regular Tiwanaku folks seemed to have had enough of this arrangement. This was a time of drought and so it was probably getting more difficult to produce crops. But Tiwanaku leaders continued to demand. Eventually, the population rebelled. They were no longer ok with their leaders gaining more and more wealth. They destroyed some of the statues and monuments. They burnt the Putuni palace. Most people left the city of Tiwanaku and went to live in the countryside.

Similar things happened in the Moquegua Valley.

This raises an important question. What happened to Tiwanaku people when their society changed so radically? Thanks to a lot of recent archaeological research in Moquegua we have a really good understanding of what life was like there after Tiwanaku leaders were toppled.

When the immigrant communities decided they didn’t trust their leaders anymore, Tiwanaku families in Moquegua left the towns they had been living in. People moved to the coast or about 20 km (12 miles) up the valley. There they created new villages. These were smaller than the towns they left. This was a time when society was changing quickly. Some people probably felt a bit unsure about what was going to happen. To protect their families, they built their new homes in places that were easy to defend, like on the slopes of hills.

Figure 16. The archaeological site of Tumilaca la Chimba. Tiwanaku people created a village here after they toppled their leaders around 1000 CE. To be safe, they lived in sites like this that are located above the river with good views up and down the valley. On the top of the hill you can see the walls of a fortress. It was built a few hundred years later.

Archaeologists call these new villages and the artifacts that we find in them Tumilaca. (See the map at the top of the page to find the location of Tumilaca la Chimba). My team has spent about 15 years investigating what life was like in these villages. We wanted to know how regular women, men, and children were affected by the big changes to society that happened about 1000 CE, and how they were responding to the changes.

To find that out we’ve excavated Tumilaca houses and analyzed the archaeological remains of people’s day to day lives. We found that people tried to keep a lot of Tiwanaku customs. They mostly built houses, made and used objects, ate foods, and buried their dead like people did before the big changes to society. Even though they had rebelled against the leaders of Tiwanaku society, the people in Tumilaca villages wanted to keep their traditions because their identity hadn’t changed.

However, there were some differences from life before. For example, when people made their pottery, they no longer painted it with pictures of the Staff God (remember him from the Sun Gate). The Staff God was associated with the leaders. When people toppled those leaders, they didn’t want to draw or see images connected with them.

Life wasn’t easy during this period of change. Analysis of human bones and teeth shows us that people’s health wasn’t as good as before. Getting hold of some materials and goods got more difficult. As society was changing, long distance trade networks were affected. Remember that alpacas and llamas really prefer high altitudes? Weavers at the Tumilaca villages used cotton more than alpaca wool to make cloth. They still liked to use wool but they saved it for special things. We think that they were being careful about not wasting wool because as connections with the altiplano were strained it became more difficult to get wool.

Even though some things were more difficult, Tumilaca villagers were building a new society. In this new society, there wasn’t as much difference in wealth and power between families. In this new society, everyone could participate in rituals because they took place in open spaces instead of on top of pyramids and in enclosed buildings.

Remember, archaeology is often the only way that we can learn about the lives of past people who weren’t wealthy and powerful. What happened when Tiwanaku people rejected their leaders provides us with a fascinating example of how huge disruptions to society affect daily life. But it also shows us how resilient people can be and how regular people, people like me and you, can make change.

Tiwanaku lecture, videos, and more from Alexei Vranich