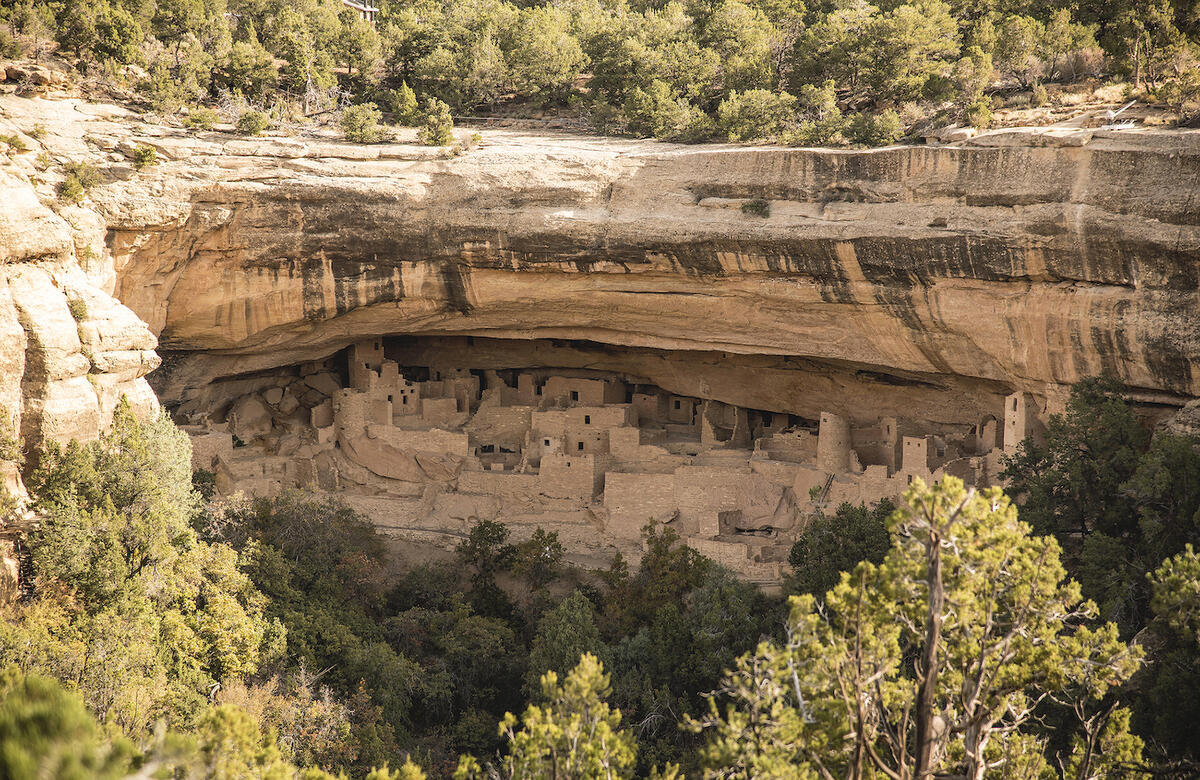

Ancestral Puebloan site of Mesa Verde

Dear Students,

Hello! My name is EB, and I’m excited to share with you about life between 1000 and 1300 C.E. in the Southwest part of what is now the United States. I’m an archaeologist at U.C. Berkeley, where I’m working on a project to understand how people in the Ancestral Puebloan world used the plants and environment around them for food, heat, and other important daily needs.

I got interested in archaeology when I was in college. Before then, I didn’t know that this was a real job! Doing archaeology means that I get to work outside and use science, storytelling, and history to learn about the past. I would love to travel to other countries to do archaeology someday, but for now, I have done lots of work inside the United States. I have spent the last seven years doing archaeology in the Southwest (mostly in New Mexico), and have gotten to participate in projects in the Northeast as well.

At UC Berkeley, I am a PhD student in our paleoethnobotany lab, which means that out of all the different material objects that tell us about life in the past, I focus on the remains of plants. I love gardening, cooking, and trees, so learning about the ways that past people did these things helps me better understand what their lives were like.

In this kit, I am going to introduce you to some details about life in the Ancestral Puebloan world. Ancestral Puebloan people were the ancestors of the Pueblo communities who live in Arizona and New Mexico today. Their societies were creative, exciting, and complicated, just like societies today. I hope you enjoy learning a bit about big urban places like Mesa Verde, and about the place where I work, called the Gallina area.

Happy reading!

EB Dresser-Kluchman

The Ancestral Puebloan people were a group of people who lived near the Four Corners from about 700 CE until the late 1200s CE. They didn’t just disappear in 1300 though! “Ancestral Pueblo” is a name that archaeologists give to people who farmed and lived across the Colorado Plateau during this time period. Their ancestors lived in the Southwest for thousands of years before 700, and many of their descendants live in Pueblos in New Mexico and Arizona to this day. Ancestral Pueblo people were different from their grandparents and great grandparents who lived before the 700s because they started building houses above the ground, and because they were very good at farming in a difficult environment.

Ancestral Pueblo people lived in small villages and at some huge sites, like Chaco and Mesa Verde. Their environment was difficult in some ways. In the northern Southwest, pinyon pine and juniper woodlands are mixed with sagebrush-covered flat areas and ponderosa forests. All these areas are dry, with unpredictable rain and snow. Conserving and using water would have been one of the main concerns for Ancestral Puebloan people and for the entire community. Mesa Verde, in Southwest Colorado, is one of the places where many Ancestral Pueblo people lived for a long time. We will focus on this beautiful site.

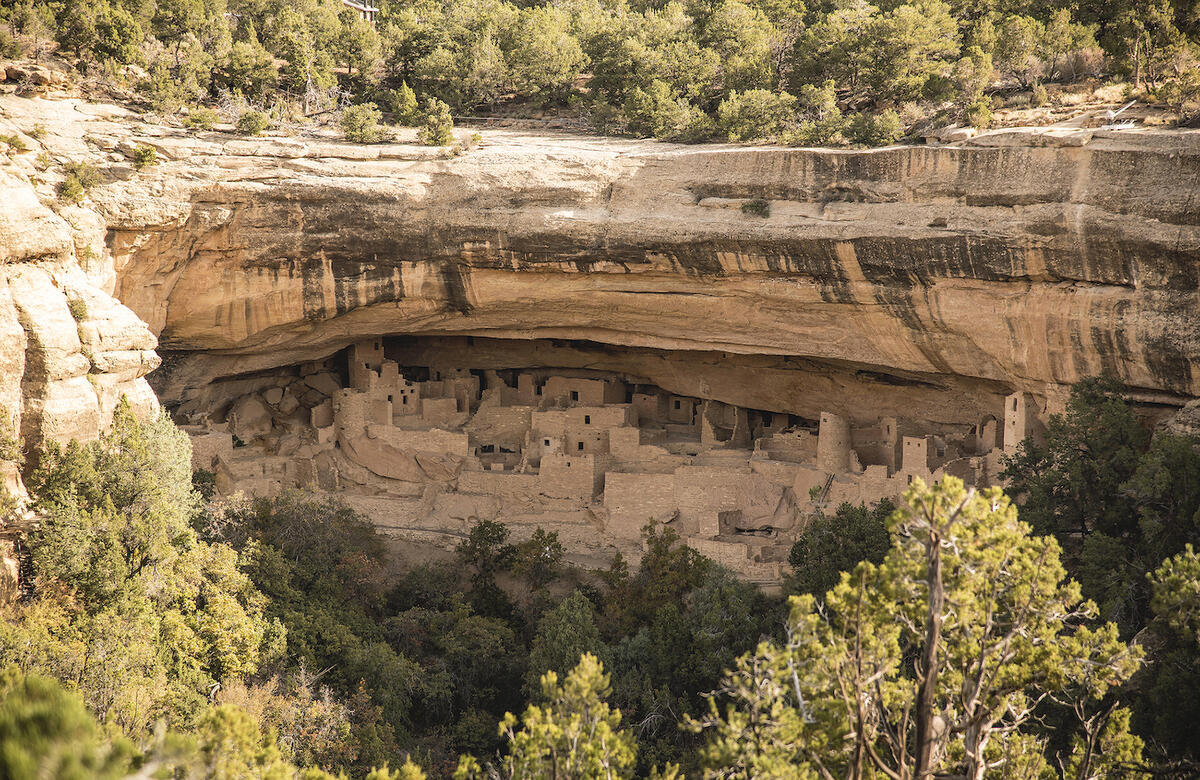

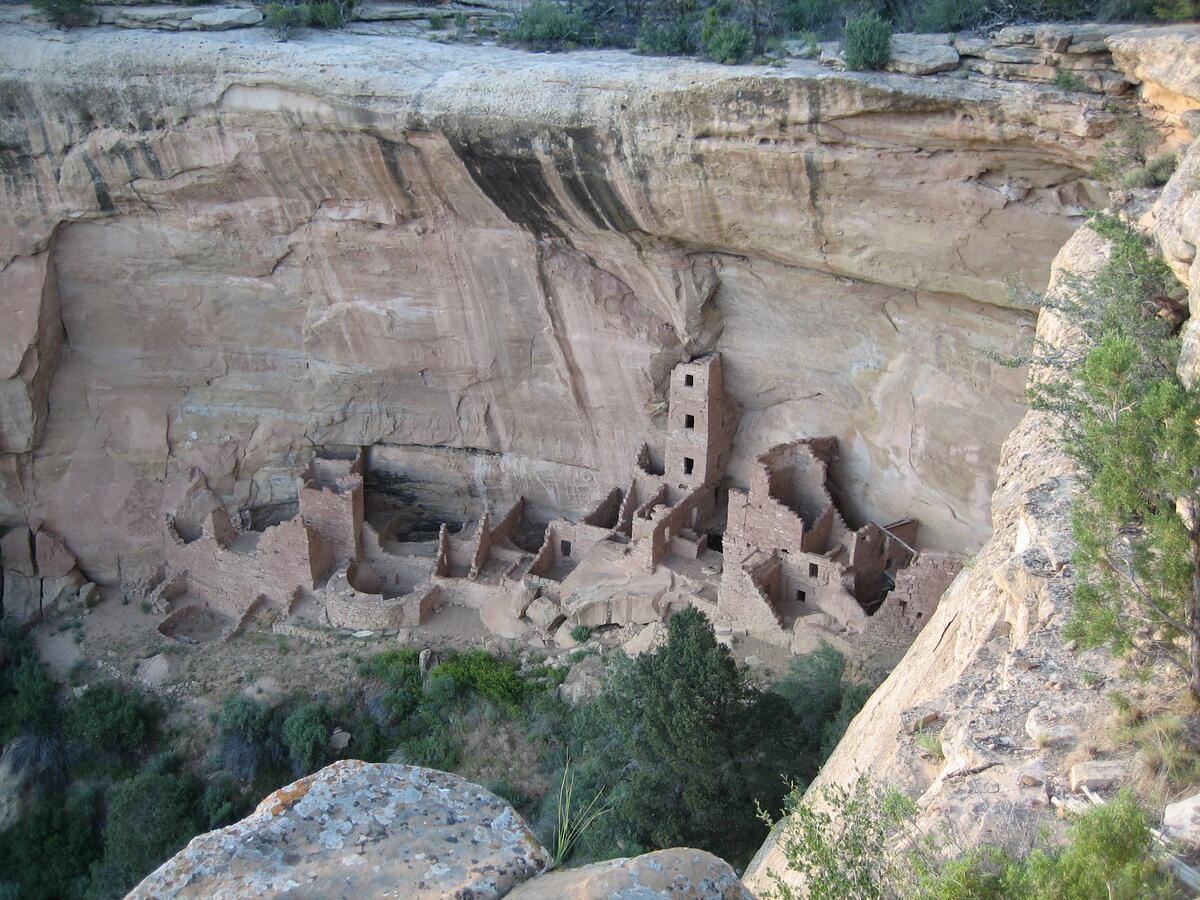

These round and square apartment-like rooms were occupied after about 1200 CE.

At Mesa Verde, your life would have been different depending on when you lived. Back in the mid-500s CE, the ancestors of the Ancestral Puebloan people, the Basketmakers, lived near this area in pithouses. Then, after Ancestral Puebloan culture emerged, there were additional changes. If you were an Ancestral Puebloan person before 1100 - say in 900 or 1000 CE - you would have lived in a house with just your family, up against houses of other families. Your house would have been built of wood timbers and adobe mud. If you were alive in 1100, you would have lived with several thousand other people in villages of connected rooms, like a giant apartment building. Those rooms were made of masonry with beautiful walls and there were underground kivas for your community’s religious practices nearby. Just one hundred years later, in 1200, you would have been moving to houses built into cliffs nearby! People lived in different areas of the Mesa Verde region at different times based on changes in the environment, population, and culture. Archaeologists are always working on understanding why exactly people chose to move each of these times.

Some things about life would have been similar no matter when you were born. At Mesa Verde, you would have lived with your mother’s extended family, and you would have dressed in hides and turkey-feather robes for warmth in the winter. You would have lived with animals too! Mesa Verde people had domesticated dogs and turkeys. Men probably spent a lot of time farming in careful fields that had to be managed specially in the dry environment. Women and men both gathered wild food, and women spent many hours grinding corn, which is hard work. Mesa Verde people also had specialties—you might have been an especially great potter, weaver, or jewelry maker. The things you made might have been used at home or might have been used in trade. Mesa Verde sites have evidence of seashells from as far away as the Pacific Coast and turquoise, pottery, and cotton from the south, as far away as modern day Mexico.

Ever since archaeologists began working at Mesa Verde, they have tried to answer the question of why people left in the late 1200s and where they went next. Different ideas have been proposed, from environmental collapse to violence, and early archaeologists thought about this leaving as disappearing from the Southwest entirely.

The idea that the people of Mesa Verde just vanished has been lingering since early archaeological research. In fact, until recently, archaeologists and historians called the people who lived at Mesa Verde and other sites nearby the “Anasazi”, a word that Navajo people used for them, which translates to ancient foreigner, or even enemy. Calling these people the Anasazi was hurtful to their descendants, who don’t see their own ancestors as foreign or as an enemy. Calling them Ancestral Puebloan, as we now do, fixes that problem, and helps us remember that these people did not just disappear! They may have moved, as all people do sometimes, but the Pueblo people have held onto their history, which includes time spent at sites like Mesa Verde.

Consultation and collaboration with Pueblo people and scholars has changed the way that archaeologists think about migration away from Mesa Verde. Now, based on Tewa oral history, researchers understand that Mesa Verde people simply moved farther east, towards the Rio Grande region of northern New Mexico, where many of their descendants still live today. Using oral history, archaeology, and soil science, archaeologists have been able to come up with new ideas about the end of Mesa Verde. Even though there was a drought at the end of the time that people lived at the site, we can see that the environment was only one of the things that led people to move. The conditions when people moved weren’t much worse than they had been before. Using archaeology that works with oral history, evidence for migration to the Rio Grande area helps answer the second question clearly: people went east.

People at Mesa Verde got most of their food from a careful system of agriculture. Corn, beans, and squash were especially important. Even though we think of those three foods as Southwestern today, they were domesticated in Mesoamerica long before the Ancestral Puebloan period began at Mesa Verde. By 750 CE, these crops had been adopted fully into Southwestern life, and corn, especially, was central to Mesa Verde life. Corn was important for calories, but it was also spiritually and culturally significant to people. At Mesa Verde, these farmed plants would have been eaten with wild foods that were gathered, as well as with meat, which was hunted.

Archaeologists recover plants from the dirt that have been charred or dried. These plant reamins, which are sometimes thousands of years old, help us understand how people fed themselves.

Even though Mesa Verde had domesticated plants and domesticated dogs and turkeys, they didn’t have domesticated animals like sheep or cows for food, so most of the meat that they ate was hunted with bows and arrows. As a child in this society, you might have learned to hunt deer, rabbits, and other wild animals for meat. If too many deer had been hunted and their population declined, you might have eaten some turkey meat too, even though turkeys were mostly kept for their warm feathers, which were used in clothing and ceremonies.

Farming was probably the job of men at Mesa Verde, who would clear mesa tops and use the land there to grow things. Ancestral Pueblo farming was based on a lot of knowledge about water conservation and land management. Special terraced gardens and grid gardens helped preserve water and warmth in soil, so that crops had a good chance to grow. The sustainable farming methods used in Pueblo history can be a great lesson about the possibilities for growing food in difficult environments today, too.

This is an example of a small terraced garden. The rock terraces hold water and keep moisture from moving downhill. Plants could be grown on the flat areas between rock walls.

Over time, people at Mesa Verde built many different types of architecture. Mostly, however, they are known for their beautiful cliff dwellings, which are built under overhangs. Many rooms, built of masonry, were grouped together in these areas during the 1200s. In these types of homes, and in villages built on Mesa tops, Ancestral Pueblo people at Mesa Verde all also built kivas, which are usually circular and built into the ground. Because kivas are a ceremonial structure, groups of people would go into their own kivas to do ceremonies. By descending down a ladder into the kiva, people were entering a special place.

People at Mesa Verde built other non-residential buildings, too, where people didn’t live. The Sun Temple at Mesa Verde is a great example of Indigenous scientific knowledge and ceremony. The Sun Temple is a ceremonial structure. The building is very exciting to archaeologists and other visitors because of its unique “D” shape. The Sun Temple also includes an area that might have worked as a sundial to mark changing seasons. However, the Temple may not have ever been finished. Based on what its architecture looks like, archaeologists aren’t sure that all of the parts of the temple were built before people moved away from Mesa Verde.

Note the multi-story buildings with windows. Some buildings were four or more stories tall! The round rooms are kivas.

All of this architecture would have been a lot of heavy work! Even the mud and beam architecture of the early 700s takes time and expertise, but the careful masonry that makes Mesa Verde so famous would have been a long job. As a community member at Mesa Verde, you probably would have cooperated to be part of this construction.

These beautifully-constructed homes in cliffs were hard to get to, but easy to defend. The small holes you see on the walls of some buildings (like the tower) are places where wooden beams once stretched across buildings to form floors and ceilings. The original roofs also no longer exist.

During the part of history that archaeologists call the Classic Period, between about 1000 and 1300 CE, most of the people in the Ancestral Puebloan world lived in centralized places with thousands of other people, much like a city today. You’ve already read about Mesa Verde, where many people came together. Lots of people lived in the area in and around Chaco Canyon as well. These people lived in villages of rooms built right next to each other, practiced their ceremonies in underground Kivas, and were part of societies that were linked in complicated trade networks. Some people weren’t part of this trend, however.

Looking out over a valley from the perspective of a Gallina village.

In the hills of central northern New Mexico, a different type of house was built by a group of Ancestral Puebloan people during this same period. These people probably moved away from places like Mesa Verde, or from other areas in 1100. Their houses look nothing like other houses in the time period. In fact, the archaeological materials from this Gallina region look so different from the rest of the Pueblo past that archaeologists used to think that these people lived thousands of years further into the past! Ever since carbon dating has allowed us to know exactly how old organic material at sites like this are, however, we have known that the Gallina people simply chose to live differently than their neighbors at the same time. We know that some people who lived in this area had links to Mesa Verde from pottery that they brought with them.

Gallina people built huge pit-houses and stand-alone, above-ground houses, mostly up in the tree-covered hills. These pictures are from the site where I am currently doing research. On the vertical wall under the tree roots, you can see the remains of a red, burned, plaster wall. On the ground under the tree and also on the lower left of the photo, you can see the original floor, made out of flat flagstones.

So, why did this happen? Why did Gallina people move, and why did they start making pit houses and stand-alone unit houses like their distant ancestors, the basketmakers? Why did they make simple pottery without the elaborate designs they might have been used to?

In order to answer these questions, it’s important to remember that people in the past were people, with families, politics, and opinions, just like us. One answer is that this group of people were excluded for some reason, so they moved to a different area and had to make do with what they had. Another answer, which I think is better supported by our data, is that these people chose to leave crowded places where they may not have had very much power, to set themselves apart. Gallina people lived in the woods and got rid of their Kivas, which suggests to archaeologists that they also took up new ceremonies and maybe different beliefs. Maybe the Gallina were like lots of people today, who move to redefine who they are, to get more resources for their families, or to just get out of the city. While the specific reasons for their refusal to act like everyone else are still unknown to us, the Gallina people are a good reminder that the Ancestral Pueblo world was diverse and complicated, just like any other society.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park from the National Park Service

Crow Canyon Archaeological Center

Mesa Verde: a home in the cliffs from SmartHistory