We are Andrés, María Clara and David and it is a pleasure to be able to write this for you.

We are a team of archaeologists studying together the ways of life of societies that lived long ago where we live today in Córdoba, Argentina, in South America. Andrés is the team leader. He studied archaeology at university, and has been interested in indigenous societies since he was a child. María Clara and David are younger. David was first a musician in an orchestra, but decided he preferred studying archaeology. Maria Clara previously studied anthropology and is now an archaeologist. We all like the fact that with archaeology we can learn about the past of these societies, learn from them and thus respect them more.

Here we will tell you what we know about the societies of Córdoba's past. People arrived here thousands of years ago and changed their way of life over time. In the beginning they were few, living only on what they hunted and gathering foods from nature. As time went by there were more and more people and they began to live in houses in small villages and to grow crops, although they never stopped hunting and gathering. It is very important to know what happened, to ask ourselves why these societies changed some of their customs and not others. We do not know why this happened in this way and we think it’s good to try to unravel the mystery. Since they knew the environment very well, we can also learn from them how to relate to it today without damaging it and improve our own way of life. We all agree that it is very exciting when in the field we discover the remains left by these societies, and then to be able to rescue them for study and then tell others what we know or show it in museums.

We hope you enjoy learning about these early Indigenous societies as much as we do!

Andrés, María Clara and David

Indigenous societies have inhabited South America for many centuries. In the south-central part of Argentina, in the Sierras de Córdoba, several of these societies lived in the past. It is a region of low mountains and large plains. Winter is not very cold, and the summer somewhat hot, which is when it rains. It is a dry environment known as Chaco. There used to be forests of trees similar to the mesquite of the Southwest USA, which Spanish settlers called algarrobo (carob, in English). These trees bear edible fruits, which were an important food source for people in their daily lives. There were also deer and a typical South American animal, the guanaco, which is related to the llama.

Around 11,000 years ago, the first families arrived in the area from the north, hunting large animals that no longer exist today, mainly glyptodonts, and some others such as guanacos. They used spears with stone points.

It was very cold (because this was just at the end of the last glacial period), but with time the weather warmed.Those big animals did not adjust to the heat and became extinct. That is why people created new weapons to hunt other animals. Many families lived in large caves, where they cooked, slept, and made artifacts, such as bone needles for sewing hides and bags, and clothing. They also made weapons and used smoothed stones to grind seeds and make flour. They also crushed red, yellow and black minerals to make paints, which they used to paint figures on rocks. They did not know how to make pottery, but they made baskets and nets from plants. We do not know if the men were the ones who hunted and the women did tasks near the caves, such as gathering fruits, working hides or making baskets. Probably both men and women cooked and raised children, as is common in other places where people have the same way of life. Many times, they buried their loved ones inside the caves.

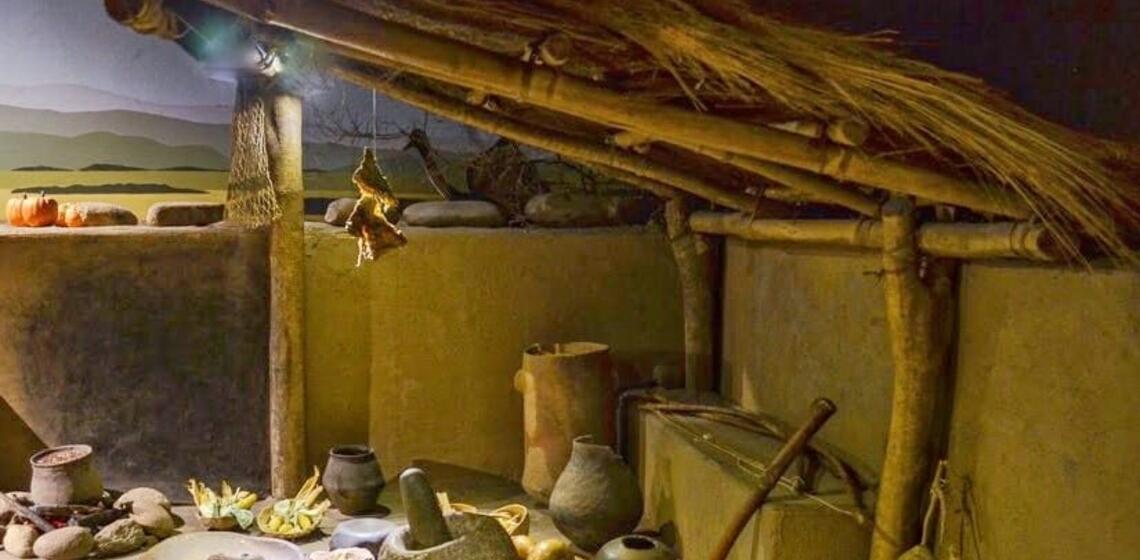

This way of life lasted a long time, but about 2000 years ago, they started making pottery and farming. We do not know why this change occurred but it had significant consequences. With ceramics, they made vessels and pots where they cooked their cultivated foods: corn, beans and squash. To make some pots they used baskets and covered them with clay. Once the pottery was fired, the basket was burned and its mark remained, which formed a beautiful pattern. From pottery, they also made figurines that represented people, both men and women. Growing grains and making pottery meant a very important change in their lives, as they improved their diet. In order to take care of their cultivated fields, they built villages of very large houses with wooden and straw roofs. These were called pit-houses because much of the house was below-ground. Nearby they dug other small pits in the ground where they stored crops to have food all year round.

We know nothing of their religious beliefs and rituals. We do know that at the beginning of summer, they had big meetings with people from different places with whom they met to celebrate, and they made a lot of food and drinks especially for those gatherings.

In 1573 the Spanish conquistadors arrived and, as in the rest of America, they dominated the communities. Many people died or were killed, their lands were taken away and they were required to work for the conquerors, so they lost their traditional way of life. However, some of the people survived and today some of their descendants are recognizing their indigenous roots, calling themselves as they used to: Comechingones [pronounced co as in "coconut", me as Ma in "Mary", chin as in "chin" and gón as in "gone": co-ma-chin-gone].

Archaeologists do not work alone. In some towns in Córdoba, citizens care about indigenous remains and are true guardians of archaeological materials, considered to be heritage. They form collections of ceramic, stone and bone elements, which are cared for in local museums. The archaeological materials that collectors rescue come from:

- Great construction works that unearth archaeological remains.

- Rescues made by collectors on expeditions through the mountains and forests

- Donations from neighbors who find them in their yards and gardens.

Many of these materials are exposed on the surface of the ground due to the action of rain, and if they are not recovered in time, they run the risk of being lost.

Collectors are familiar with scientific archeological research, but also make their own interpretations of archaeological heritage. They do not always coincide, but they contribute to what archaeologists think. For example, a characteristic artifact from the indigenous groups in the area are ceramic figurines of men and women, sometimes of children. They have a body, legs, and head, but no arms, and are about 4 inches tall. They have a lot of detail on their faces, and have skirts, shirts and hats, as well as ornaments such as necklaces, tattoos and hairstyles with braids and headbands. Archaeologists think that each figurine represented a different person, possibly dead, and that making them was a way of remembering them.

Some collectors we spoke with told us that they believe the figurines were charms, formerly used in rituals, but that now they are objects that bring luck or can scare people. Daniel, a collector, says that a statue that he found is very special. Walking in the forest on a very hot day, Daniel felt that something important was going to happen, and he was moved when he found the head of a strange statuette, with something of an animal and something of a person. He knelt down, picked her up, and his heart skipped a beat because in that instant he felt that it was a magical object. Daniel brought the figurine to his house, even though he was scared. During the night, he heard noises and thought about getting rid of it. One day he asked it, "bring me luck in the lottery or I'll send you back to the forest," and that same day he won. From then on, he was no longer afraid and the figurine continued to bring him luck. However, Daniel knows that the figurine is heritage and today it is in the Museum of his city. Now everyone can see it, and the municipality has taken it as its symbol and it is part of the identity of all citizens.

The men and women of this society knew very well the environment where they lived. They knew precisely where the best places to hunt were and what the habits of the animals were. They also knew where to find the best stones to make their weapons and good clays to make their vessels. Fundamentally, they knew the landscape, the climate, and other natural phenomena very well. They knew that in the Chaco, in the summer, sometimes it rains in one place and but doesn’t rain a short distance away. Other times hail falls in one area but not across the field. In the past, invasions of large numbers of grasshoppers that ate all crops were also very common. To avoid all these problems, and using their knowledge of the environment, they planted their corn in separate places from each other. Therefore, for example, if hail fell on one side, it probably would not fall on another; or the grasshoppers would eat only a part of their crops.

They also knew where the best places in the environment were to set up their villages: they did it a little distance from the rivers because in the summer there are suddenly very dangerous floodwaters. As it is a landscape with mountains, they chose places to build their houses halfway between the plains and the highlands. That way they could go to the plains to take care of their crops and look for fruits in the forest or go hunting in the mountains and return home the same day.

The construction of the houses was very particular. They are known as "pit-houses". Instead of building walls, they dug a large rectangular pit in the ground and roofed it with branches and straw. From the outside, this looked like a roof sitting just above the ground. On the inside, it was sort of like a basement room with an opening around the top of the wall, just below the ceiling. These houses were cool in the summer and warm in the winter, and they were protected from the wind. As only the roof was visible, the houses were almost hidden in the landscape. From a distance, their location was indicated by their cornfields or by the smoke from the fireplaces. We don’t know how many people lived in each house. When the Spaniards arrived, they were amazed at their size and said that eight horses and their riders could fit inside a single house! It is possible then that there were many people living there. The same family lived in each house for a long time. Always one house was close to another and they formed villages. There were villages with few houses and other very large ones of up to 40 houses.

Everyday life happened around and inside the pit-houses. From the ceramic and stone objects found in archaeological excavations, we know that inside they ground corn and prepared food. Stone instruments, arrowheads and bone knives were also found. Under the floors they buried some of their dead, perhaps the most beloved. Outside the houses were the places where they made stone, leather and bone objects. Right there, they also made baskets with plants and the vessels and pots.

For the groups in the Córdoba mountains, some plants and animals in the environment remained consistently important sources of food. Even though time passed and they adopted agriculture, guanacos and carob fruits were among their favorite foods. They also hunted some deer and collected eggs from suri, an ostrich-like bird that is characteristic of South America. Once they shifted to living villages, they also added cultivated plants, such as corn, squash, and beans to their meals.

Some of the seeds and fruits they collected in the forest are very sweet and were used for different things. Carob fruits, one of the most important fruits they gathered, were first left to dry for several days and then crushed to make flour using a mortar and pestle. With the carob flour and water, they made a sweet cake that was left to dry in the sun, without the need to cook it. They also ground the fresh fruits of different trees and made small balls with their hands that they ate as candies. They also prepared a syrup with the fresh fruits by boiling them in water. With the crushed fruits in the summer they made drinks: they added water to them and made a soft (non-alcoholic) drink, and if they left the crushed fruit in the water for several days they obtained beer, which they drank at social gatherings.

The beginning of summer, the time when the carob fruits were ripe, was very important for all the people. Men, women and children from all over the village gathered to work together to collect the fruits. At that time the great gatherings with people from other villages were held and they celebrated by drinking carob beer and soft drink. Today, the descendants of these groups are taking up these customs and once a year a popular festival is held for this reason.

With cultivated plants they made different foods, such as stews where they mixed corn, squash and beans, sometimes with meat. One of them was made at the time when the corn was tender and freshly harvested. The corn kernels were separated from the husk and mixed with pieces of squash, and cooked in water for many hours. Finally a thick soup was formed, which is called humita. A beer is prepared with corn, which is very common throughout South America and is known as chicha. They also prepared a sweet non-alcoholic drink. Another kind of stew was made with corn, squash, beans, and small pieces of meat, which were also cooked for many hours. This dish is known as locro

Archaeological studies suggest that women were the ones who prepared the flours. We know this based on studies of skeletal remains. Women’s bodies show modifications due to heavy activity in the arms and wrists. It is not known whether men and women cooked at the same time. However, the Spanish said that the drinks were made together by men and women.

Many of these native foods are still made today on special days. Above all, locro and humita are cooked on holidays in Argentina, especially Independence Day and Labor Day, when families and friends get together to celebrate.

In the mountains of Córdoba there are many caves where the indigenous people painted the rocks with different drawings. They painted figures of animals, such as guanacos, lizards, jaguars, owls, foxes, native ostriches, and condors. They also drew lines, points, and circles. The drawings are white, black, red and some yellow. The paints were made with minerals that were ground to powder and then mixed with animal fat.

Many times they depicted the guanacos running in herds, with their young. Of the native ostriches they only drew their footprints. Sometimes they painted people, some with feather ornaments on their heads and backs, and armed with bows and arrows in their hands, as if they were ready to shoot. Other times they drew people covered with feather and fur costumes, with masks on their heads. Archaeologists believe that these were men or women with special powers and abilities to heal other people, who are known today as shamans or medicine men and women.

A unique and very interesting painting is the one that shows an encounter between Spaniards and indigenous groups. Some of the Indigenous people have very long spears and others are in groups holding hands as if confronting the Spaniards. The Spanish invaders were painted in great detail; you can distinguish their clothes, weapons and horses

These caves with paintings were special places. They are not easily visible to the naked eye and are usually hidden in the forest and far from houses. Possibly, they were meeting places where they performed rituals according to their beliefs.

"Comechingones de Córdoba: fuentes históricas para contar el pasado silenciado" from UNciencia

"White Carob Flour" from Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity