My name is Caitlin Davis and I am a graduate student in archaeology at Yale University. I study the Southern Maya Region, between the Pacific Ocean and volcanic highlands of Guatemala and El Salvador. I first became interested in archaeology as a child when I read about Machu Picchu in Peru, which led me to discover the many other cultures of the ancient Americas. My favorite thing about archaeology is the way it connects me to people who lived very differently than I do. Being able to see and touch the objects made by people from long ago helps to think about them as real people who had vibrant, complex lives just like ours. I especially love reading ancient hieroglyphic writing, which allows me to read about the lives of these people in their own words.

I’ve selected some of my favorite monuments from the ancient city of Cotzumalguapa, Guatemala, for you to discover. This city, located under the shadows of smoking volcanoes, was home to a unique civilization for over one thousand years. The hieroglyphs of Cotzumalguapa remain undeciphered, which means that we don’t know how the writing system works or how to read it. While the general idea of an inscription might be suggested, no one in the entire world can actually read them. I hope these monuments from Cotzumalguapa help you feel closer to the people of ancient Guatemala. Maybe they’ll even inspire you to decipher the script and become the first person in over a thousand years to know what it says!

Best wishes,

Caitlin Davis

Cotzumalguapa is an ancient city located on the coast of Guatemala in the sloping hills between the volcanoes and the Pacific Ocean. The modern name for the city comes from the Nahuatl language of Central Mexico, based on the root word cozatli which means weasel. However, this name was given to the site by Nahuatl speakers who later moved into the region, and the people who lived at Cotzumalguapa probably called it by a different name. The people of Cotzumalguapa lived in the shadow of volcanoes, relying on volcanic rock (basalt) and volcanic glass (obsidian) as raw materials. The fertile volcanic soil proved useful for growing crops like cacao, and many of the earliest levels of the site are buried underneath thick volcanic ash.

The first people settled at Cotzumalguapa around 400 BCE. Not much is known about the earliest Cotzumalguapans because the buildings they constructed are located underneath later buildings. Cotzumalguapa grew, and the people at the site eventually adopted the new political system of divine kingship around 100 CE. They carved monuments expressing these new ideas, like El Baul Stela 1, that look similar to those found at other ancient cities in Guatemala. These monuments, along with ceramics, tell us that they had relationships with other people who lived along the Pacific Coast and up in the mountainous Highlands.

As Cotzumalguapa grew bigger, its people began to interact with cities farther away. Art and ceramics tell us about relationships with Teotihuacan, a massive city in Central Mexico, and with the Maya people who lived to the east in Guatemala. A large collection of monuments was built around 400 CE in the neighborhood of Bilbao, which was probably the religious center of the city. Large buildings were also constructed at El Baul, where the ruler and other important people may have lived.

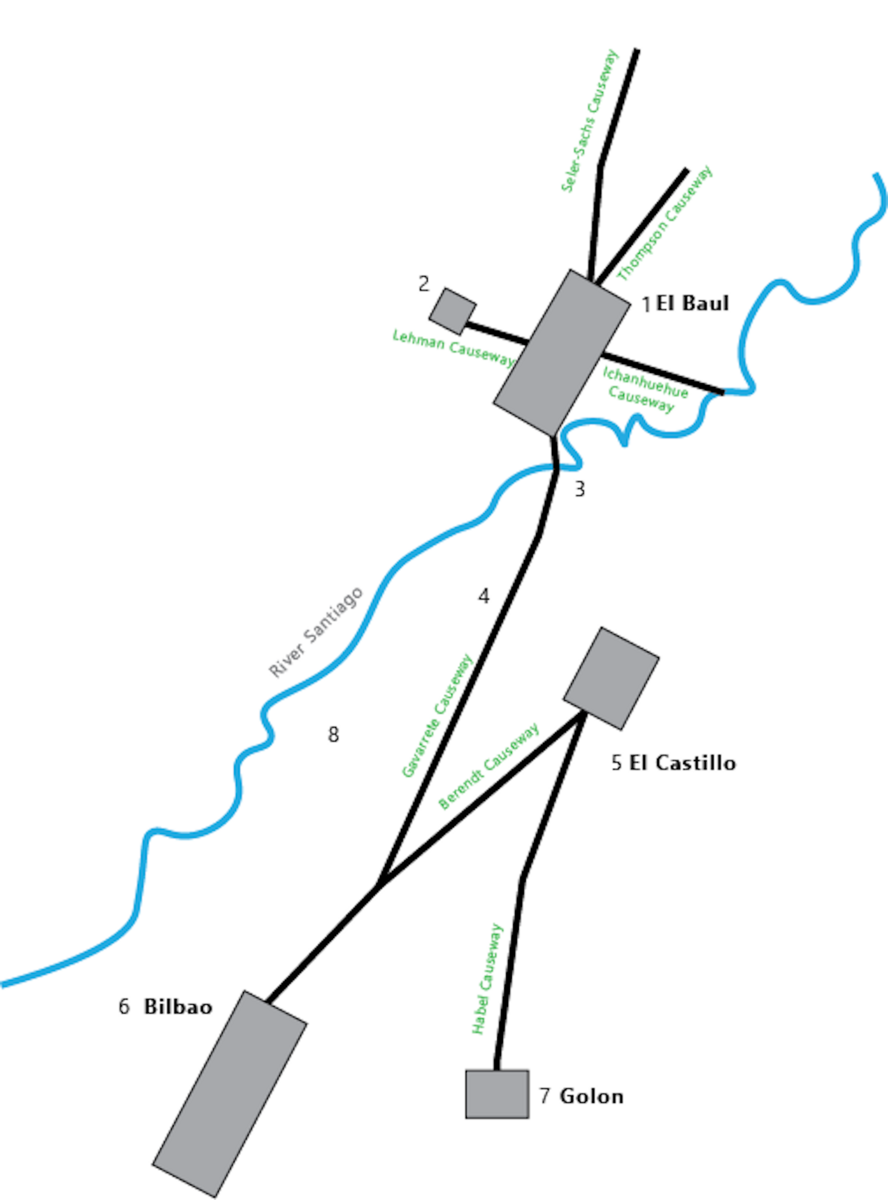

From 600 – 900 CE, Cotzumalguapa was a very important city on the coast. More monuments were added to Bilbao around 650 CE, and people across the region started to carve monuments using the art style and writing system used at Cotzumalguapa. Causeways and bridges were built connecting Bilbao and El Baul, with the houses of common people located around them. While we know very little about the lives of common people, we know that a city of this size must have had craftspeople, traders, and farmers living within it. Excavations at El Baul show that some obsidian workers worked very close to the palace – possibly making obsidian tools directly for the ruler. The people of Cotzumalguapa probably had many languages and cultures, as people from across the coast brought their families to the largest city in the region.

After 1000 CE, many people moved away from Cotzumalguapa. The people who stayed stopped making large buildings and monuments, of architecture and monuments ceased at Cotzumalguapa. Ceramics tell us that people still lived in the area, but their culture must have been very different than that of the earlier Cotzumalguapan people.

Figure 1: Map of Cotzumalguapa

Unraveling the relationships between cultures is an important part of archaeology. Over the past hundred years of research on Cotzumalguapan history, archaeologists have debated how the Cotzumalguapans were related to two cultural groups: the lowland Guatemalan Maya and the Central Mexican Teotihuacanos.

The relationship between Cotzumalguapan people and Maya people has been discussed for over a century. This is because of the discovery of a stone monument, El Baul Stela 1. This monument recorded an early calendar inscription, equivalent to 37 CE in our calendar, which was written in the same recording system used by later Maya people. This calendrical system did not become popular until around 400 CE, and was predominantly used in the lowlands to the east of the volcanic ridge. Cotzumalguapa was separated from the lowlands by a series of volcanoes, so we can see why scholars may be confused to find such an early monument in this region. In fact, some scholars even denied it recorded such an early date at all and suggested it had been written later! Other scholars believed the inscription and date were as early as it said and suggested that the Cotzumalguapans were the root of early Maya civilization and culture.

Scholars also once believed that the Cotzumalguapans were related to the Mexican city of Teotihuacan. Teotihuacan was a very powerful city with far-reaching influence across Mesoamerica. Some early researchers thought that Cotzumalguapa may have originally been controlled by Teotihuacan and they theorized that it achieved independence from Teotihuacan around 600 CE. An important argument in support of this idea was the visual similarities between the art produced by Teotihuacan and Cotzumalguapan people. For example they had similar depictions of a google-eyed god associated with rain. However, recent archaeologists have questioned the Teotihuacan colonization of the Pacific Coast of Guatemala, exploring other explanations for the shared art styles.

Cotzumalguapa challenges how we understand and interpret ancient cities. Should we think of Cotzumalguapans as Mexican because their art is similar to Teotihuacan? Should we think of them as Mayan because they use a calendar used by later Maya people? Or should we think about Cotzumalguapa as Cotzumalguapan? Most scholars now believe that the Cotzumalguapan people should be understood as their own distinct culture, rather than interpreted through the lens of another culture.

Figure 2 shows images of deities that look similar but are from different Mesoamerican cultures. Image #1, below, is a Cotzumalguapan monument that has been described as Tlaloc. Tlaloc is actually an Aztec water deity from hundreds of years in the future with a similar goggle-eyed face and long fangs (Image #5). What similarities do you see between these rain deities from different Mesoamerican cultures? What differences do you see? How should archaeologists think about these similarities and differences?

Figure 2

Compare these images of “rain” gods with similar physical features from different Mesoamerican cultures.

1. Cotzumalguapa El Baul Monument 15, Museo El Baul, 600 – 900 CE.

2. Teotihuacan, Tepantitla Mural, Teotihuacan Archaeological Zone, 600 CE.

3. Mixtec, Rain God Mask, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1200 – 1300 CE.

4. Maya, Dresden Codex, Saxon State and University Library Dresden, 1200 CE.

5. Aztec/Mexica, Codex Ixtlilxochitl, National Library of France, 1550 CE.

One of the things Cotzumalguapa is most famous for is its stone monuments. While many of these monuments were taken to Germany in the 1800s by archaeologists, some remain in situ, and others are likely undiscovered (still buried beneath the ground). One sculpture even lies at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean after it fell off a ship heading to Germany in 1880!

As in much of Mesoamerica, monumental art was related to both religious beliefs and political power. Carved monuments at Cotzumalguapa often depicted rulers and supernatural beings performing rituals while wearing fancy clothing, and are sometimes accompanied by hieroglyphic or calendrical inscriptions. The iconography of these monuments is complex, but often involves themes of decapitation, sacrifice, and cacao

Cacao is a plant that is indigenous to the Pacific Coast. It is also where chocolate and cocoa come from! Today we think of chocolate as a tasty treat, but in Cotzumalguapa cacao was associated with wealth and power. Cotzumalguapan rulers were often depicted with cacao in their headdresses, linking them to the important plant.

Death, decapitation and human sacrifice are also prevalent in Cotzumalguapan art. Cacao pods are sometimes depicted with faces, representing severed heads. Sacrifice was an important component of Cotzumalguapan religion, as in other Mesoamerican religions. Human sacrifice was important because it kept the gods happy, and those who were sacrificed were often of high status. Many Mesoamerican cultures believed that the gods had sacrificed themselves in the act of making the world and that humans had an obligation to repay these sacrifices. Human sacrifice was seen as essential to maintaining the universe, and the more valuable the offering, the happier the gods would be.

The Cotzumalguapan people participated in shared styles of art and writing across Guatemala, but also developed traditions unique to themselves. Most of the writing at Cotzumalguapa probably relates to history, both real and mythological.

El Baul Stela 1 is one of the most interesting monuments at Cotzumalguapa. It shows man in a headdress facing a column of hieroglyphs. The man depicted was probably a king or mythological ruler. The hieroglyphic text, one of the earliest examples of the Maya Long Count calendar, records a date that corresponds to our year 37 CE. The entire monument was probably painted red, as suggested by the remaining red color. El Baul Stela 1 is important because it records a specific historical date, which is rare across Mesoamerica at this time. Because of damage to the monument, what happened on this date in 37 CE is a mystery. However, it shows that the early Cotzumalguapan people had some connection with the later Maya who used this calendar.

Later on, around 600 CE, the Cotzumalguapans developed a new writing system entirely unique to the area. These symbols, once carved into stone monuments decorating important political and religious buildings, remain a mystery to modern archaeologists. No one in the entire world can read the Cotzumalguapan writing system! However, by looking at patterns in hieroglyphs we can suggest that it records the names of people, places, and gods. Do you think it’s possible to decipher Cotzumalguapan hieroglyphs?

Cotzumalguapans enjoyed sporting events like boxing and a very popular ball game played by many Mesoamerican cultures. We don’t know the exact rules of the game, but we do know that it was important for social, political, and religious reasons. The ball game is depicted on many monuments from Bilbao, which were once arranged in a row for religious processions. Many people on these monuments wear a wide belt around their waist, called a yoke. This was probably worn so players could hit the ball with their hips without getting injured. Real stone yokes have been found at cities along the Pacific Coast of Guatemala.

Physical evidence of a ballcourt is underneath the ground north of El Baul, where Cotzumalguapan people likely engaged in the sport. The stone court includes benches and a wall used in playing the game. A stone ring was also found nearby – one can imagine players using their hips to pass the ball through the hoop. The ball court was also decorated with statues like El Baul Monument 70, which shows a human figure transforming into a coyote.

Cotzumalguapans also enjoyed other sporting activities. El Baul Stela 27 depicts two men engaged in conflict, each wearing gloves. This scene has been interpreted as a boxing competition based on the mask worn by the larger figure. Ritual boxing remains an important activity today in some Mesoamerican cultures, where men still wear animal masks. Based on their costumes, the men may also be playing pelota mixteca, a game which involves hitting a ball with a glove.

You have already read about the changing narratives explaining how Cotzumalguapa is related to other cultures, but what do we know now about intercultural interactions at Cotzumalguapa?

Some scholars believe Cotzumalguapa was part of a network of city-states at an early point in its history, around 100 CE. As a city-state, Cotzumalguapa interacted often with other cities on the coast and probably negotiated trade networks, alliances, and wars. Kaminaljuyu, a large city in the Guatemalan Highlands, shared styles of ceramic and sculpture with Cotzumalguapa which shows evidence of a relationship between these cities.

What about their relationship with Teotihuacan? Scholars now believe Cotzumalguapa was NOT a Teotihuacan colony. In fact, the similarities between Cotzumalguapan and Teotihuacan art may be related to Cotzumalguapan resistance to Teotihuacan colonization. Many other cities on the coast were colonized by Teotihuacan, meaning that Cotzumalguapa may have been influenced by the Teotihuacan style. However, the Cotzumalguapans may have incorporated select parts of Teotihuacan art into their own distinctive art style as a way of rejecting Teotihuacan colonization and asserting their independence. This is an example of cultural syncretism

While we cannot turn to Cotzumalguapan writing for information on intercultural interaction, some monuments do provide hints. El Baul Monument 30 is one object that can help us understand more about the relationship between Cotzumalguapan and lowland Maya people. The monument shows a figure with a headdress associated with the Maya on one side, and a figure with traditional Cotzumalguapan braided hair on the other. The figures are engaged in conversation, as demonstrated through the scrolls that emerge from their mouths. While we do not know what these people were discussing, the monument shows that Maya and Cotzumalguapan people were in contact with each other. Their sizes depict them as equals and demonstrate that their interactions were significant enough to carve into stone.

El Baul Monument 30

Figure 6

Examine the details of this image.

1. The man on the left wears a feathered headdress in the Maya style, known from monuments in the Peten rainforest.

2. The man on the right is distinguished by his hair braids and earring style, both of which indicate he is a Cotzumalguapan. Their dress indicates they are men of high social status. We may imagine them as representatives of two communities having a meeting.

3. The Maya and the Cotzumalguapan men are engaged in conversation, represented by the flowering vines emerging from their mouths. These vines are a symbol of prayer and poetry at Cotzumalguapa.

4. Cartouches which may have once held hieroglyphs surround both figures. These glyphs may have recorded the name of these individuals, or the date their meeting took place.

"A Corpus of Cotzumalhuapa-Style Sculpture, Guatemala" by Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos in FAMSI

"Sounds in Stone: Song, Music, and Dance on Monument 21 from Bilbao, Cotzumalguapa, Guatemala" by Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos in The PARI Journal